The World Bank yesterday delivered yet another bad news for the economy as the Washington-based multilateral lender pared back Bangladesh’s growth forecast for this fiscal year by 1.5 percent to 5.2 percent.

“Bangladesh was hard hit by spillovers from the changing global environment,” said the WB in the latest edition of its flagship publication Global Economic Prospects.

The country was priced out of global energy markets and unable to meet the energy needs of households and businesses.

“The government responded to high global energy prices with blackouts and factory closures to reduce energy consumption, stopped purchasing vehicles, and made it harder to purchase luxury goods, among other measures to preserve international reserves.”

Rising energy costs and supply constraints saw industrial production contract in September from its peak in March, it said, adding that the rising cost of imports almost doubled the trade deficit since 2019.

The deficit would have been larger were it not for the robust demand for Bangladesh’s garment and its growing share in the global market.

Since early June, the Bangladeshi taka has depreciated by 18 percent and foreign exchange reserves have declined by $8 billion, pushing inflation to 8.7 percent (year-on-year) in December, it said.

The heady cocktail of rising inflation and its negative impact on household incomes and firms’ input costs, as well as energy shortages, import restrictions and monetary policy tightening means growth is expected to slow to 5.2 percent in fiscal 2022-23, down from 6.5 percent forecasted earlier in June last year.

“This is down from 7.2 percent growth in the previous year, but is expected to pick up again and return towards its potential pace in fiscal 2023-24,” it added.

The forecast though has been dismissed by Finance Minister AHM Mustafa Kamal.

In a meeting with the new WB country director Abdoulaye Seck yesterday, hours before the lender unveiled the report, Kamal was informed of the lower growth forecast for this fiscal year, The Daily Star has learnt from people familiar with the discussion.

“It will never ever be less than 6 percent,” Kamal told Seck, said people quoting the finance minister.

Last month, the government revised down the growth forecast from 7.2 percent to 6.5 percent due to the impacts of the Ukraine war, bringing it in line with the projection made by the Asian Development Bank (6.6 percent) in September last year and International Monetary Fund (6 percent) the following month.

“5.2 percent is not bad growth if you assess the global situation,” said Zahid Hussain, a former lead economist of the WB’s Dhaka office.

But the downgrade from the previous fiscal year is marked.

“It is because of four crucial developments in the economy over the past six months,” he said.

The factors are the dollar shortage, which has unleashed a host of problems, inflation that has eaten away people’s purchasing power and caused a decline in the real wage, global inflation that has made imports prohibitive, and supply-side problems in the form of energy crisis.

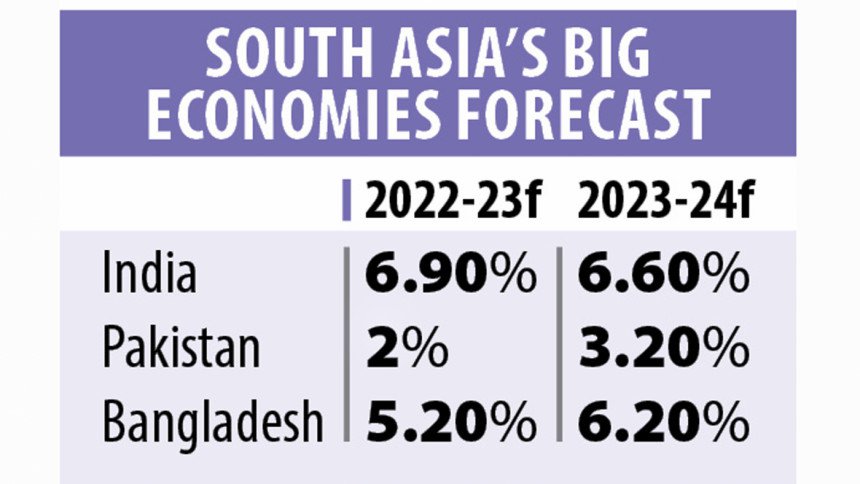

Bangladesh is not the only economy in South Asia to see a downward revision in growth forecast this time.

Growth in India is projected to slow to 6.9 percent in its fiscal 2022-23, a 0.6 percentage point downward revision since June, as the global economy and rising uncertainty will weigh on export and investment growth. India is expected to be the world’s fastest-growing major economy.

Pakistan is forecast to grow at 2 percent in fiscal 2022-23, half the pace that was anticipated last June, and faces challenging economic conditions, including the repercussions of the recent flooding and continued policy and political uncertainty.

Bhutan will grow at 4.1 percent and Nepal at 5.1 percent.

The economies of the South Asia region continue to be adversely affected by shocks emanating from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, including higher food and energy prices, and by the tightening of global financial conditions as central banks in the region and elsewhere act to fight high inflation, the WB said.

Subsequently, growth in the region is projected to slow to 5.5 percent in 2023, from 6.1 percent the previous year, on slowing external demand and tightening financial conditions, before picking up slightly to 5.8 percent in 2024.

Growth is revised lower over the forecast horizon and is below the region’s 2000-19 average growth of 6.5 percent. This pace reflects still robust growth in India, Maldives, and Nepal, offsetting the effects of the floods in Pakistan and the economic and political crises in Afghanistan and Sri Lanka.

The global economy is projected to grow by 1.7 percent in 2023 and 2.7 percent in 2024.

The sharp downturn in growth in the face of elevated inflation, higher interest rates, reduced investment, and disruptions caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is expected to be widespread, with forecasts in 2023 revised down for 95 percent of advanced economies and nearly 70 percent of emerging market and developing economies.

“Given fragile economic conditions, any new adverse development — such as higher-than-expected inflation, abrupt rises in interest rates to contain it, a resurgence of the COVID-19 pandemic, or escalating geopolitical tensions — could push the global economy into recession. This would mark the first time in more than 80 years that two global recessions have occurred within the same decade.”