It all began with a search for ‘phuti karpas’ – muslin’s unique cotton plant which is known to have become extinct. However, starting in 2014, government and private collaboration and initiative have given us a chance at the fabric’s revival. Here is a detailed narrative of what happened beyond the spotlight to bring back muslin to the centre stage again

Workers are weaving Muslin sarees at the Dhakai Muslin House at Narayanganj’s Tarabo. At the height of its fame, a yard of fable fabric of Dhaka once could fetch prices ranging from £50 to £400, equivalent to roughly £7,000 to £56,000 today, with even the best silk costing 26 times less. But in the face of British greed and brutality, the industry soon crumbled. Now, if sold, the muslin will again fetch a premium. Photo: Rajib Dhar

Workers are weaving Muslin sarees at the Dhakai Muslin House at Narayanganj’s Tarabo. At the height of its fame, a yard of fable fabric of Dhaka once could fetch prices ranging from £50 to £400, equivalent to roughly £7,000 to £56,000 today, with even the best silk costing 26 times less. But in the face of British greed and brutality, the industry soon crumbled. Now, if sold, the muslin will again fetch a premium. Photo: Rajib Dhar

It all began with a search for a ghost, one glorious, beloved and more enigmatic than anything before it.

For a long time, we were in the dark about its origin and some of the greatest wordsmiths couldn’t resist making it their muse.

Amir Khusrau, considered by many as the “father of Urdu literature” and also the “founder of Qawwali” (a devotional form of singing by the Sufi), in his last book before his death, “Nihayatul-Kamaak, ‘The Height of Wonders,” said the apparition was so transparent and lightweight, if someone dared to don it, they would “look as if one is in no dress at all but has smeared the body with pure water.”

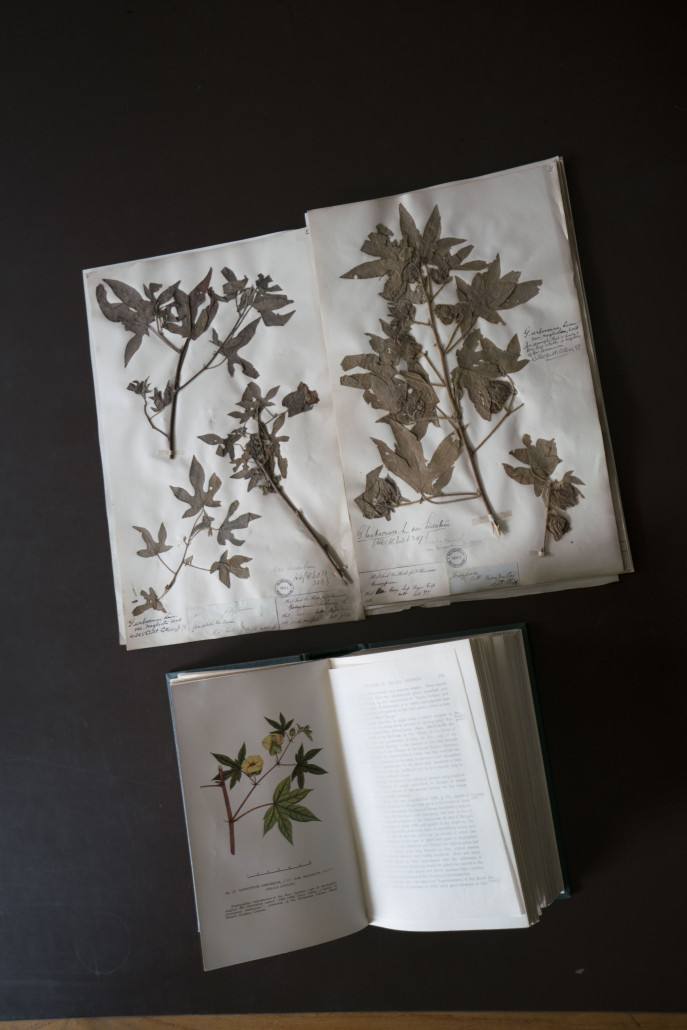

Other imperial poets said it was “baft hawa” (or ‘woven air’). Bengal’s phuti karpas produced the cotton used for the finest muslin. Correctly identified by George Watt as Gossypium Arboreum Var. Neglecta, the plant lies embalmed in the Kew Garden’s Herbarium. Photo credit: Shahidul Alam, Drik, Bangladesh. Item courtesy of Kew Gardens.

Bengal’s phuti karpas produced the cotton used for the finest muslin. Correctly identified by George Watt as Gossypium Arboreum Var. Neglecta, the plant lies embalmed in the Kew Garden’s Herbarium. Photo credit: Shahidul Alam, Drik, Bangladesh. Item courtesy of Kew Gardens.

And then, just like that, the spirit vanished into thin air, never to be seen again for 200 years. Its demise was not simply spiritual, but physical.

The advent of the British colonisation of India in 1765, beginning with the acquisition of the diwani (revenue collection) of Bengal, sounded the death knell of its legendary fabric, muslin. The colonial apparatus, whether in the form of the East India Company (1785-1858 CE) or direct rule by the Crown (1858-1947), was a vast extractive machine. On one side, both the Company and the Crown squeezed the farmers and the weavers, while on the other, a factory-produced, mass-product ‘muslin’ rolled off the newly invented power looms in Lancashire cotton mills. British cotton textiles flooded not only the European markets, but the captive Indian ones as well, and aided by an array of punitive taxes and tariffs, succeeded in bringing Bengal’s handloom cotton industry, in particular muslin, to its knees.

Soon, along the riverbanks, ‘phuti karpas’ – muslin’s unique cotton plant – became extinct. Famines swept through the previously fertile land of Bengal, and spinners and weavers fled from their villages or starved. East Bengal’s muslin became a dusty, desolate memory and only jamdani (one of five varieties of muslin) survived to the present times, albeit in a coarser form.  Unchanged over hundreds of years, these tools are used for making the fine toothed shana (reed) through which the warp threads pass on the loom and form part of a number of tools used for making the jamdani cloth. Photo credit: Tapash Paul, Drik, Bangladesh.

Unchanged over hundreds of years, these tools are used for making the fine toothed shana (reed) through which the warp threads pass on the loom and form part of a number of tools used for making the jamdani cloth. Photo credit: Tapash Paul, Drik, Bangladesh.

In 2014, two years after the Mayan prediction of doom passed, whispers began of a reincarnation of this phantom.

The entire world was enraptured: the muslin miracle was in the making, they said.

Now, almost a decade later, while the muslin hasn’t returned to full form, its ghost is less translucent than before, hinting at a comeback, more real than ever.

The fabled fabric is back, its rebirth involving a host of colourful characters bound together by their determination to do the impossible.

Verse 1: Against all odds

“You picked a new direction in the blink of an eye. My time away just made perfection, did you think I died?”

The Stepney Trust, a UK-based charity, worked on the importance, from 2011, of Bengal-manufactured materials in the history of London’s fashion industry, even performing ground-breaking steps to weave 80-count handloom cotton cloth. Weaving the magical motifs within the body of a jamdani sari, in Rupganj, Bangladesh, by adding the supplementary weft thread within the body of the cloth by the dextrous use of a kandul (pick made of bull horn) on the loom. Photo credit: Tapash Paul, Drik, Bangladesh.

Weaving the magical motifs within the body of a jamdani sari, in Rupganj, Bangladesh, by adding the supplementary weft thread within the body of the cloth by the dextrous use of a kandul (pick made of bull horn) on the loom. Photo credit: Tapash Paul, Drik, Bangladesh.

At the time, most other weavings were done between 40-60 counts. Muslin, which some claimed was created by mermaids and fairies, had a cotton count (weight of 1,000 meters in grams) between 250-1,200, a number nearly impossible to attain.

Saiful Islam, the then Chief Executive officer of Drik, was approached by the Stepney Trust in 2013, about holding a show on muslin in Dhaka.

The Trust had done great work, but they lacked vital details – the now-extinct cotton plant ‘phuti karpas’ from which the yarn was collected, the villages where it was made and the craftspeople involved in its arduous manufacturing process.

In early 2014, Saif formed a team that started the pioneering task of reviving the muslin’s history and its connection with Bangladesh. The team collected plants, collated research from over 20 countries, documented processes and curated a host of information, images and artefacts. Master weaver Al Amin weaving classical motifs onto the body of a high count new muslin jamdani sari, on his loom, at Rupganj, Bangladesh. He performs these complex designs from memory using the ancient techniques and his own hereditary skill. Photo credit: Shahidul Alam, Drik, Bangladesh.

Master weaver Al Amin weaving classical motifs onto the body of a high count new muslin jamdani sari, on his loom, at Rupganj, Bangladesh. He performs these complex designs from memory using the ancient techniques and his own hereditary skill. Photo credit: Shahidul Alam, Drik, Bangladesh.

Saif’s research soon led him on a different and more challenging trajectory. Why only research the story when the revival of the fabric was an option that would firmly stake our claim on the fabric? He decided to involve other players, ie Aarong, the Bangladesh Ministry of Culture, the Bangladesh Handloom Board, the Cotton Development Board and other resources.

In 2015, Saif met Monzur Hossain, a professor at the Botany Department of Rajshahi University and shared all their collected data regarding muslin. Monzur was excited by the prospect and promised to come on board. He was later approached by then Deputy Minister of the Jute and Textile Ministry Mirza Azam and the secretary of the same ministry to work on a government project to revive muslin. Monzur had some experience in the field.

A while ago, while working on a different project, the botanist was asked by a Japanese colleague if he could revive the lost fabric.

“I heard about muslin from my grandfather and father, and also studied a bit about it. But my knowledge wasn’t comprehensive. I asked the man for three months’ time to do some research and gauge whether it was possible or not,” he recalled.

When the deadline came, Monzur boldly declared that it was possible. But there were some bottlenecks. They needed samples of original Dhaka Muslin, funding, resources and most importantly, they had to find phuti karpas, the prime ingredient without which Dhaka Muslin is impossible to make.  Mahajan (broker) is the center of attention at a weekly Government approved jamdani market place where sellers vie for his approval. These saris are sold on to the city markets for a hefty added commission by him. Photo credit: Wahid Adnan, Drik, Bangladesh.

Mahajan (broker) is the center of attention at a weekly Government approved jamdani market place where sellers vie for his approval. These saris are sold on to the city markets for a hefty added commission by him. Photo credit: Wahid Adnan, Drik, Bangladesh.

In the face of many hurdles, the team ultimately failed to make any practical progress. Now, a new chance fell upon Monzur, one which came with a solution to all the challenges he faced in his previous venture.

The professor was made the head of a seven-member team, which comprised experts from the Handloom Board, engineers from the Bangladesh University of Textiles and others. He was tasked with making a proposal for the project and after some time it got approval.

By 2017, funding began to come through slowly and work began towards the revival of Dhaka Muslin.

Verse 2: All eyes on me

“They pursue me like a dream. But I’m known to disappear before your eyes just like a fiend.”

Finding something as elusive as the phuti karpas, a plant that had not been seen for two centuries sounds like a quest in a role-playing game.

The reality of the journey, too, matched the genre well.

After putting a project team together, Saif started off by initially meeting a range of experts in Bangladesh including Professor Sharifuddin Ahmed, Department of history in Dhaka University, a number of senior crafts researchers and officials from the Bangladesh Handloom Board (BHB), the Cotton Development Board, Bangla Academy, Asiatic Society, Bangladesh Agricultural University in Mymensingh and the Bangladesh National Museum. His overseas visits led him to Jordan, South Africa, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Turkey, the United States, the United Kingdom and India including institutions such as the British Museum, V&A, Bath Museum, Kew Gardens, National Craft Museum in India and many more.

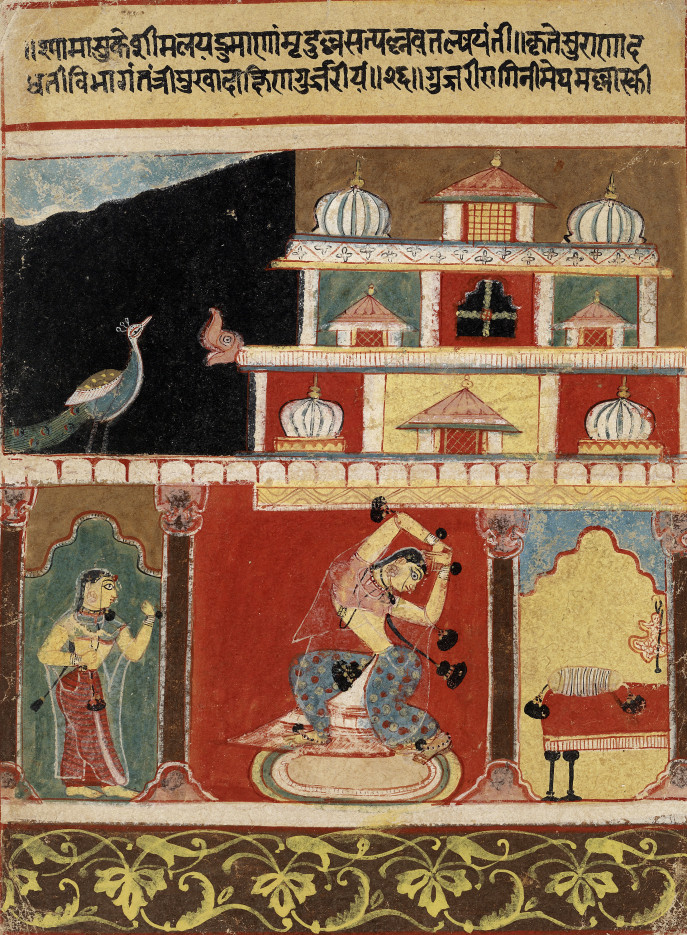

The name phuti karpas constantly came up during the conversations. Dancers wearing muslin as an outer garment where the transparency of the cloth is depicted as a white line by the artist. Photo credit: Saiful Islam, Drik-Bengal Muslin, Bangladesh. Painting courtesy of Yale Center for British Art/Yale University Art Gallery.

Dancers wearing muslin as an outer garment where the transparency of the cloth is depicted as a white line by the artist. Photo credit: Saiful Islam, Drik-Bengal Muslin, Bangladesh. Painting courtesy of Yale Center for British Art/Yale University Art Gallery.

A sample of the plant had been collected and identified by William Roxburgh (1751-1815), a famous English botanist. According to historical records, it was said to grow on a specific length, around 40 kilometres, of the mud-lined banks of the Meghna River.

The plant wasn’t just nourished by the flood-borne nutrients from the Assamese hills. It also relied on the care and skill of the farmers in that area who undertook the painstaking process of converting ‘karpas’ (raw cotton in Bangla) into ‘tula’ (clean cotton).

Bengal Muslin team’s hunt for the plant commenced in mid-2014. Armed with paintings of the phuti karpas and satellite maps of the rivers they journeyed on the water of the Meghna and Sitalakhya. Unlike other cotton plants, this one had five lobes instead of three, along with a red stem which helped it stand out – it was time to cast their net and hope to snare it.

Their first date with destiny was in Gazipur’s Kapasia, a name which was associated with ‘karpas.’ The area had also been known for its cotton industry since the first century.

The riverine journey would encompass a route from Kapasia to Mymensingh in the north and down to Barisal in the south. He and his team also visited the border areas near Assam and the Chittagong Hill Tracts where the elusive cotton plant was likely to grow.

Along the way, the team began distributing leaflets showing a painting of the original phuti karpas. It also had a contact number, which could be called if anyone came across the plant. The information guaranteed a reward. The leaflets were distributed to farmers, land owners, bazaars, shops, farms and tea stalls along the team’s way.

There were often calls and the team rushed to the spot only to be disappointed.

The journeys were often by boat as they scoured the river banks. If there were answers to be found, it would be here in these muddy settings. Out of the collected samples, six showed the closest physical characteristics. However, Bengal Muslin agreed that a legend needed to be grounded and science needed to be activated.

Scientists in the UK had confirmed that DNA matching needed to be done between plant samples and not cloth samples. Saif decided to match the DNA of fossilised plants with their collected sample plants and for this purpose, he visited both the Kew Gardens and the Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden at Kolkata.

The team conducted extensive DNA analysis at a university in the UK and the results returned a 70% match with the original plants preserved in the UK. Armed with this breakthrough, in 2015 they planted the seeds with the assistance of the Bangladesh Cotton Development Board on a ‘char’ (island formed through siltation) near Kapasia.

The prodigal plant had finally returned to its roots.

The cotton they grew was sent to India, where it was mixed with their fine cotton and spun on an Ambar Charkha to produce yarn of 250, 300, 350 and 400 counts.

In February 2016, muslin returned to Bangladesh as the Muslin Festival was inaugurated at the Bangladesh National Museum by the Hon. Ministers for Finance and Culture. The book, ‘Muslin. Our Story’ was launched and a culture show at Ahsan Manzil and a month-long exhibition commenced which was attended by many overseas experts and visited by over one hundred thousand people during its duration.

The history of muslin was brought alive to the audience through the exhibition and 300-count saris with classical motifs, hand-woven by Drik-Bengal Muslin’s master weaver Al Amin, were on display for the first time in Bangladesh. A remarkable journey had a befitting reward for the country’s craft revival.

“Our scientific results were shared with the Bangladesh government, cotton and handloom board officials and we held the ‘Revival of Muslin’ seminar highlighting the methodology we had followed,” Saif said.

In 2017, Professor Monzur, the then director of The Institute of Biological Sciences, RU, started on the trail of the same plant.

“I decided that I would start by talking to artisans who work with cotton. I would then trace the cotton which produces the finest fabric. During my research, I found that some scientists had suggested that the phuti karpas existed in Northeast India,” he said.

The team searched all over the country from Gazipur to Bagherhat to Chattogram and even found a few rare varieties of cotton, including Egyptian Giza cotton.

But the one they longed for was nowhere to be found.

Around the same time, Foreign Minister Shahriar Alam posted on his Facebook about the muslin revival project and the search for the plant.

“A former student of mine, who lived in Kapasia, saw the post and contacted me. ‘Sir, are you really looking for that yarn?’ I said yes and he told me that Kapasia was the centre of the plant,” recalled Monzur, who requested the student to send him a sketch of the original phuti karpas– Gossypium Arboreum Var. Neglecta.

The search went on for years. In the meantime, Monzur visited India and other countries, but his efforts abroad did not bear any success. But, he never had to cross countries in the first place. The plant was here in Bangladesh all along.

Monzur’s team had collected dozens of wild species of cotton from across the country.

One of them, found in Kapasia, “turned out to be the one.”

“The variety we found in Kapasia is the actual Phuti Karpas,” said the professor. “The region was once called Titabari, which was a major centre for phuti karpas cultivation along with Junglebari and Bajitpur,” he said.

“It has been a highland for a long time, which is suitable for phuti karpas cultivation. And that’s why Kapasia was on top of our list for places to search for the plant.”

But the team also needed original Dhaka Muslin samples to verify their find. They visited the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the world’s largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts, and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.27 million objects.

“The museum has over 300 samples of muslin with at least 70 of Dhaka Muslin.” The team got to study original Mughal-era Muslins.

Verse 3: Resurrection

“But I’m back reincarnated, incarcerated. At the time, I contemplate it is the way that God made it.”

Monzur believes his work has uncovered a match much closer to the original.

The government’s Tk120 million project has found samples from Kapasia with a match rate of above 90%, with “some deviations.” He said, “We followed a three-step verification process: morphological character analysis, DNA analysis and spinnability analysis.

The processes also included 17 fibre character analyses and genomic analyses of the cotton species.

“The original material – muslin fibre – that we had was low in quantity. We could not measure the strain of the fibre as the piece was quite old. But the micronaire value [a measurement of the thickness of the cell walls of cotton fiber] or finesse of fibre was almost matchable. The marker DNA is a complete match without any change.”

The professor refused to share details of their DNA analysis, which according to him, is the first of its kind to be done in the country.

He said, “I do not think anyone here has done a Chloroplast DNA test from ancient fabrics. We have submitted a patent application for our research.”

“The thesis of our research, currently under review, is also due to be published within a few months,” he added.

Monzur, however, concedes that their revived cotton is still not a 100% match to the original Phuti Karpas.

“We will try to fix the deviations in the next phase of the project,” he said.

Verse 4: Still I rise

“Somebody wake me, I’m dreaming, I started as a seed, the semen. Swimming upstream…”

Muslin manufacturing skills generally were compartmentalised along religious lines.

Hindus were mainly engaged in spinning yarn, while the majority of weavers were Muslims, especially of jamdani (one of the muslin’s varieties). This meant that, despite the fact that muslin had vanished, core weaving skills remained intact among the Muslim weavers of East Bengal, surviving through the 1947 Partition (East Pakistan) and again in 1971 (the Liberation War). What has remained in present-day Bangladesh are the jamdani weavers clustered around Dhaka, such as Noapara, Ruposhi, Tarabo, Kajipara, Mahimpur and Boalmari. They continued to produce jamdani but due to commercial pressures were weaving much lower count, ie 30-84 count.

The process to achieve a high count, especially with a delicate yarn such as muslin, required expert weavers.

Unfortunately, such weavers had almost been lost to the history pages.

Saif said, “A major concern for our team in 2015 was whether Bangladesh had any weavers with the talent to weave 200 and over count threads. By contacting over a hundred weavers and sifting through their products, we selected five, out of which only one could complete the 300-count sari in early 2016.”

He added, “It gave us an amazing sense of accomplishment. Since then we have trained more than 20 weavers. They were trained on the job and to motivate them we also gave them some knowledge of muslin’s history, their community’s connection to it and its past glory.”

The government’s muslin revival project turned to textile engineers who would work with spinners, mostly from the Cumilla region. The khadi, along with the jamdani, were two relatives of muslin. Spinners acquainted with either of the fabrics would thus be the perfect choice to work on muslin.

“Their ancestors used to spin jamdani and muslin. Muslin and jamdani are the fruits of the same tree without much difference. One is called ‘figure muslin’, meaning Muslin with different kinds of design and arts. They are very expensive clothes. On the other hand, pure muslins were plain white clothes. We selected those khadi weavers for the revival task. It took us two years to train six weavers.”

Even after the training, the arduous production process for the fibre took longer.

Eventually, in 2022 the Muslin Revival Project reached an envious thread count of 731 for 30 of the clothes it has made so far.

An establishment was set up in Rupganj – Dhakai Muslin House – where the clothes are being made.

“We visited a lot of places for the original Muslin sample. And of the 40 samples we saw in the London Museum, not one was above 500 counts. I think our team can reach 800 thread count. We have 300 weavers working now. Their expertise has grown, so if they keep up the work, it won’t take long.”

On future prospects, Saif said, “At the initial stage, the Government of Bangladesh, Ministry of Culture and Aarong supported Bengal Muslin for its research, weaving and exhibition. Afterwards, the Handloom Board formed its own project with government funding and claimed the rediscovery of Muslin.

This is a significant achievement but unlike us their DNA matching process, production techniques and final product have not been shared with other scientists and crafts experts as yet. Neither have they acknowledged the knowledge gained from Bengal Muslin.”

In the meantime, Bengal Muslin using its own resources continues to grow cotton, spin the yarn in India and weave high-count cloth, which has been a pioneering and groundbreaking achievement for Bangladesh and the world of crafts.

Ayub Ali, project director of Bangladesh’s Golden Tradition Muslin Yarn Making Technology and Recovery of Muslin Fabrics as the project is now called, also chief planning office of BHB, said the first phase – which ends in 2023 – focused on reviving the phuti karpas, the fibre and the technology needed for the Bengal Muslin.

The second phase is ensuring the plants being used are easier to cultivate.

“We will also distribute phuti karpas seeds to farmers in Sreepur and Kapasia of Gazipur, and Rajshahi to encourage them in cultivating the plant. Their production cost will be borne by us. The government has also allotted almost 51 bigha land in Mymensingh for cultivation.”

Verse 5: Our claim is until the end of time

“I was born not to make it, but I did. The tribulations of a colonised kid.”

At the height of its fame, a yard of Dhaka muslin could fetch prices ranging from £50-400, equivalent to roughly £7,000-56,000 today, with even the best silk costing 26 times less.

But in the face of British greed and brutality, the industry soon crumbled.

Now, if sold, the muslin will again fetch a premium and there will be enough to be around for all involved.

Saif, who credits Drik with being the single largest contributor to the muslin revival initiative said the purchase by the British Museum, the world’s leading museum, was highly significant. “It is recognition for Bangladesh, its craftspeople, Bengal Muslin and its project members, that we have broken through the glass ceiling and achieved this level of appreciation for our efforts”.

He said there had been an exchange of emails before reaching an agreement. The British Museum had approached Bengal Muslin for sample swatches, publications and cotton samples for public display.

Although the entire exchange was cost-neutral, the purchase will be displayed in one of their partner gallery’s from 2023 onwards. Another international project ‘Around the World in 80 Fabrics’ partnered by the Smithsonian has taken muslin pieces from Bengal Muslin on a global tour in 2022.

“Overall, muslin is extremely arduous and time-consuming to make, thus it is an extremely expensive item of fashion wear. To date, some connoisseurs of saris and fashion design have purchased saris, scarfs, cloth for fashion…etc. from us, but it is not yet a profitable venture.

Prior to the internet or the print medium, muslin was a global brand. I believe with proper promotion and design, the cloth can achieve profitability due to its enormous and universal brand appeal, though not on a very large scale,” explained Saif.

Project Director of the BHB’s endeavour Ayub Ali said he expects commercialisation of Muslin to begin within six months of launching the second phase, although he believes it won’t be affordable for all, who said, “Muslin was never a product for low-wage earners. It takes tremendous effort and work to design and produce a muslin sari. Currently, it takes up to seven months.”

He estimates the average Muslin clothes to cost between Tk 6-7 lakh.

“The samples – from the UK’s Victoria and Albert Museum – were in the range of 300-500 counts. We have been able to manufacture up to 758 counts,” he added.

Professor Monzur also feels muslin is commercially viable, but the thread count doesn’t need to be too high.

“There might be some customers who are willing to buy that much fine [730-count] clothes. But for commercialisation, 500 count is enough. In our country, the finest fabric is considered to be 120 counts [Jamdani],” said Monzur.

According to Monzur, the market already exists.

“Many people have contacted me about buying our product, irrespective of the price. They only wanted to know when they could buy the muslin.”

All stakeholders, however, feel the more private investment is the best way forward for the fabric.

Ayub said there is also a plan to privatise muslin production, with many having shown an interest.

“It [muslin production] can be handed over to entrepreneurs…anytime in the distant future. We will also prepare for that. As part of opening up the technologies, we will train their weavers, spinners, etc. We are preparing to share the production technology with all.

“However, as the Bangladesh Handloom Board has been given the Geographical Indicator for its muslin, the board will certify whether the products made by private entrepreneurs are original muslin or not.”

So, what lies in store apart from scaling up?

Saif says, “Muslin is more than a product, it is part of our heritage, our identity. In the recent past, I was invited to see the Royal Collection, which was an eye-opener. We at Bengal Muslin are committed to telling its story in our voice, in bringing recognition to our artisans who are the true heroes and in reviving all forms of muslin that brought us such fame in the past. Inspiration begins at home.”